The Origins of the Thomas Hardye School

Who was Thomas Hardy(e)?

The le Hardy family migrated to Jersey from Normandy in the twelfth century, owing to their pro-English sympathies, which appear to have continued to cause problems - an Edmond Hardy is recorded as being ‘ostage des peskeuers de Grantchamp’ in 1419! A John Hardy migrated to England in about 1490, and his son Thomas, of Toller Whelme, married Joan Ferret (possibly Feret, another Jersey family) of Cerne. They had two sons – Edmund who became, by his second marriage, the lineal ancestor of both Admiral Hardy and Thomas Hardy the novelist, and our Thomas, who had one daughter, Thomasina.

From 1568 Hardy, who was then in the service of Sir John Paulet, is recorded as having property in both Weymouth and Dorchester. On the death of his father in 1561 Hardye’s mother had married John Browne of Frampton, where Hardy died in 1599, having given his last house, now the White Hart in Melcombe Regis, to his nephew (Sir) John Browne. Hardy’s name acquired its final ‘e’ in 1861, courtesy of Messrs. Shipp and Motson, editors of the third edition of Hutchins’ History of the Antiquities of the County of Dorset!

How did the school come into being?

The Dorchester Free School was built in 1567-9, (on the site of the Hardye Arcade in South Street) by the efforts of the townspeople, as a Protestant grammar school, designed for the free education of local boys in (Latin) grammar prior to university, as an expression and consolidation of the Protestant ‘revolution’ in a town where Catholic support lingered, as elsewhere, during the later decades of the century.

The school could not hope to rival foundations like the Sherborne or Wimborne Free Schools, with their considerable private and royal endowments, and in 1579 the town, for reasons probably financial, ‘bestowed’ the school on Thomas Hardy, hoping that his endowment would encourage others to help provide the funds needed to keep it going. As the commemorative plaque in St Peter’s church states, Hardye supplied the means to pay a preacher, a schoolmaster and usher – the essential elements of Protestant re-education of the population.

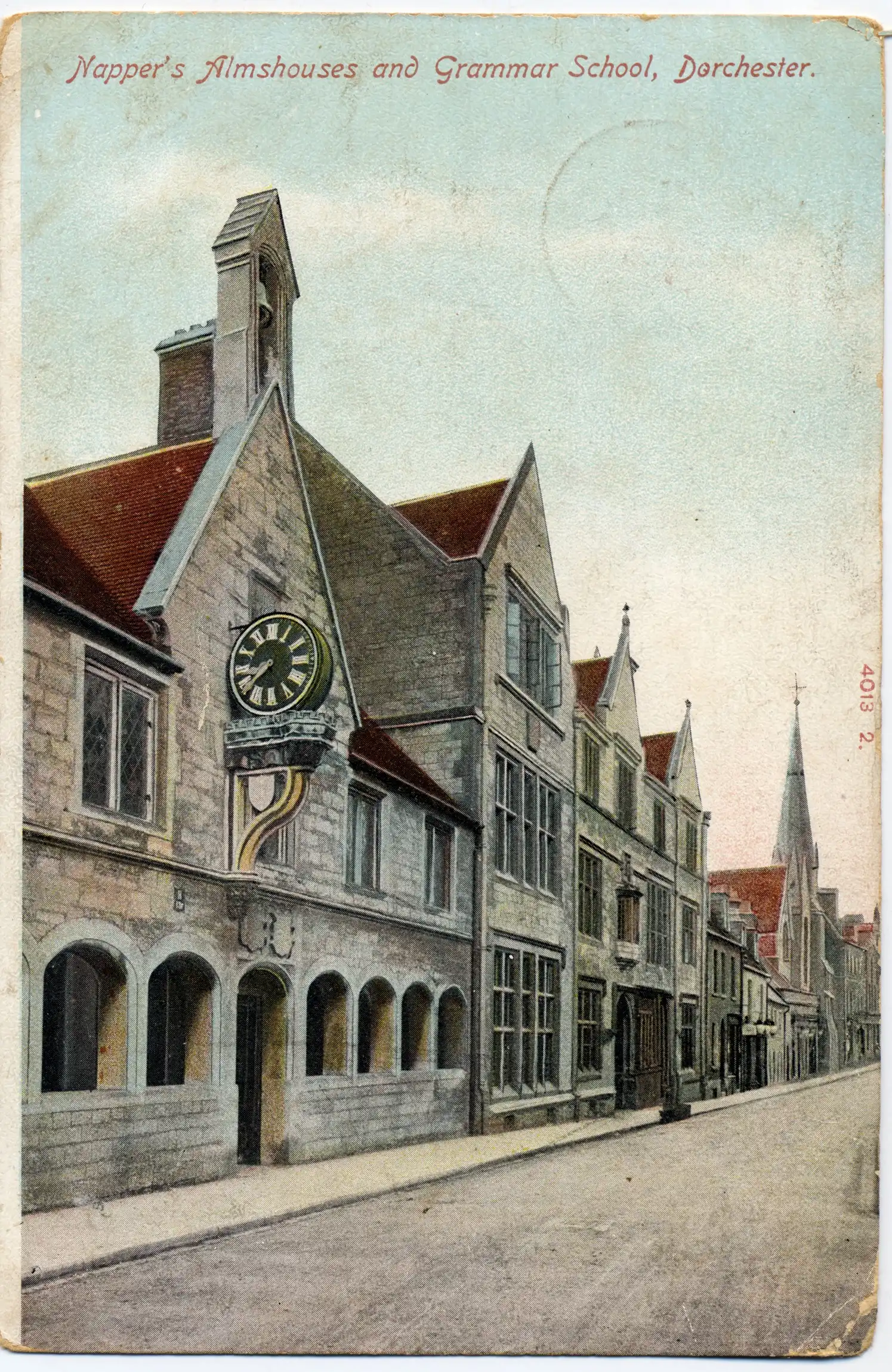

Although Robert Napper donated property adjoining the school to house an usher, or under-master, no-one else followed Hardy’s example, with the result that the school was generally short of funds throughout its history. Hardy’s endowment only supplied ‘some competent Stipend for the Maintenance of one Learned man to be a Schoolmaster and one other to be an Usher, for the necessary education and instruction of Children in all degrees in good Discipline’.

The school, which incorporated materials from ‘Chubb’s school house’, was a substantial stone building; the walling stone of the street front came from the Portland beds at Upwey and the freestone for the schoolhouse behind came from the recently opened Poxwell quarry. This quality of building did not prevent it from being badly damaged in the fire of 1613. By 1618 it had been rebuilt by Robert Cheeke, one of the two Puritan leaders of Dorchester, again largely at the town’s expense, but also at his own.

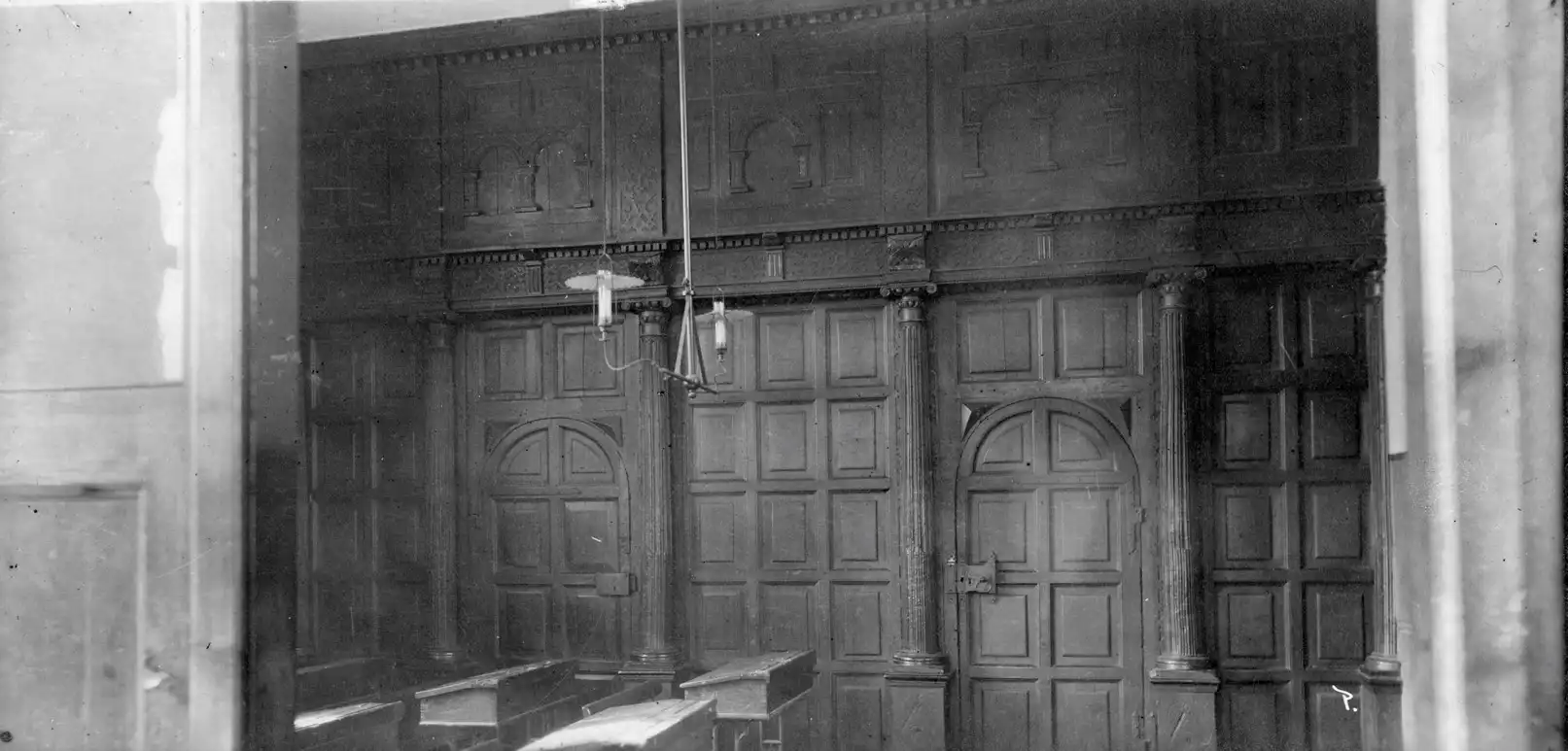

At this time the oak screen was added to the west end of the schoolroom, and the Queen’s arms restored to the exterior; these two items, now on display at the Thomas Hardye School, are all that is left of the C17th school. In the room above the schoolroom, (after Cheeke’s widow was found alternative accommodation!) the town library was installed, which was catalogued in 1631, and which contained a number of valuable works which unfortunately began to disappear quite quickly!

After the Restoration, the last Puritan master, John Stephens, was ejected (he had already been ejected from Bristol Grammar School!), and the Free School became a small Anglican country grammar school run by a series of pluralist clergymen who seem to have paid little attention to the state of the buildings, which were almost in ruins by 1824, and seem to have required almost continuous repair for the next fifty years.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, in competition with the Academy of William Barnes, and later the County School at Charminster, the school with its predominantly classical curriculum suffered, though, unlike many grammar schools at this time, managed to keep going. The last Master of the Free School, from 1846-1879 was Thomas Ratsey Maskew; he gave his name to two characters in Moonfleet by John Meade Falkner who attended the school for a year in 1869.

The Dorchester Grammar School

As was common during this period, the school was from time to time almost entirely devoid of pupils, and was lucky to survive; it was eventually closed for rebuilding in 1879 by the Charity Commission. It re-opened in 1883 with the official title of Dorchester Grammar School, with an imposing new Tudorbethan front by Crickmay, but retaining the original schoolroom behind, with a further storey on top. This school was not demolished until 1965. It had been known as ‘Hardy’s Grammar School’ in the nineteenth century to distinguish it from other schools in the town – after 1885 this became ‘Hardye’s’ with the newly-added final ‘e’, in local directories. Slowly the school grew, building more accommodation including science labs, on the premises between South Street and Charles Street.

Following the Balfour Act of 1902, as education was increasingly funded by the State via the newly- formed County Councils, the school gradually prospered, and eventually moved from the increasingly crowded site in South Street to a healthy site on land purchased from the Duchy of Cornwall, on the hill at Fordington: in 1928 the new school buildings were opened by the Prince of Wales.

Secondary Education in Dorchester

‘Hardye’s’ continued on the Fordington site as a boys’ grammar school matched by the ‘Green School’ or girls’ Grammar School in Queen’s Avenue, in about 1930. The Butler Education Act of 1944 gave rise to the Dorchester Secondary Modern School in 1945, at the end of Queen’s Avenue. The three schools became two comprehensive schools, Hardye’s boys’ at Fordington and Castlefield girls’ on the Secondary Modern site, in 1980; these were fed by the two Middle Schools, Dorchester Middle School taking over the Green School site, and St. Osmund’s being purpose-built on the SW edge of the Hardye’s site.

It was not until 1992 that the merger of the two comprehensive secondary schools created The Thomas Hardye School on the Castlefield site which fulfilled the dream of the sixteenth-century Burgesses of Dorchester in offering, in the one school, ‘the necessary education and instruction of Children in all degrees in good Discipline’, as had been proposed in the Deed of Endowment 430 years ago in 1579.